Doping in sport: why the last 20 years should give us hope in battle against cheats

July 25, 2017

In the latest of his reflections on 20 years in the sports industry, Adam Paker gets to grips with doping in sport

It would be easy to paint the last 20 years as a story of lost innocence, in which our naïve sense of the Olympian ideals of sport were shattered by doping scandal.

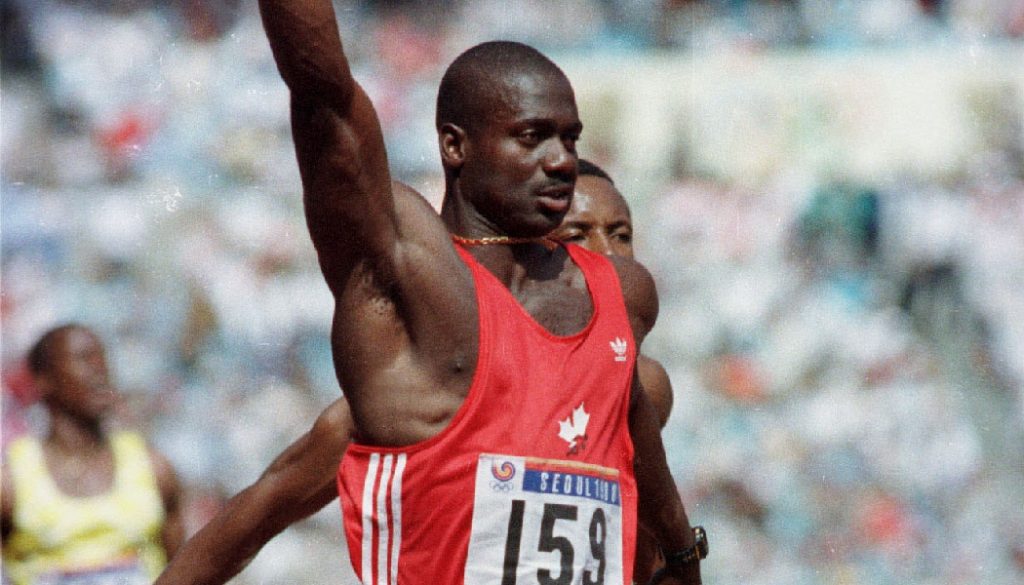

But back in the late 90s, as I was starting out in the industry, we were in fact far from naïve. It had been a decade since one of the real seismic shocks in the history of sports cheats had hit home – the discrediting of the Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson at the Seoul Games.

We were also not new to the idea of State-sponsored doping. Following German reunification, evidence came to light in 1993 that East Germany had been at it since 1971.

What really changed was our sense of the scale and extent of the problem. Looking back, much has been uncovered about past abuses, such as those of the US Olympic Committee in the 1980s, as published by Sports Illustrated in 2003.

At the same time, the bravery of whistleblowers and investigative journalists has lifted the lid on doping abuses perpetrated by individuals, whole teams such as U.S. Postal Service Pro Cycling Team and then, in 2014, one of the most successful of all sporting nations, Russia.

The revelations have taken a wrecking ball to some of our most cherished icons of sport – Lance Armstrong, Maria Sharapova and Marion Jones to name but three from a long list.

The integrity of whole sports is now under threat and doping has become one of the persistent talking points of major sports events such Le Tour.

We have a sense that more bad news is inevitable and that more athletes, sports, and whole countries will be implicated in doping scandals some time soon.

Despite this seemingly unstoppable torrent of bad news, the last two decades give us hope for sport.

Let’s remind ourselves that the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) did not come into existence until 1999, since when it has done a huge amount to raise standards of doping control and to co-ordinate the war on doping.

But more is now needed, including – as I see it – three key ingredients. First, a genuinely zero tolerance approach is required by sports governing bodies when it comes to doping – however unappealing the geopolitical battles this may entail.

Secondly, WADA, currently 50% funded by the IOC, needs to be independent. Finally, more funding – for example, the UK’s anti-doping agency receives only £5.5m from the State, yet with that it is expected to protect the multi-billion pound industry that is British sport.

There is no panacea to doping in sport, but we have learned a great deal about it in the past two decades. We can use this to take the fight to the drugs cheats.